Sainte-Foy, a Québec City suburb

“Try to learn English and shorthand typing,” my father told me in 1959, when I insisted on enrolling in the classics course at Sainte-Foy High School. “Philosophy, my dear girl, is just shovelling clouds. You’ll do much better if you chose something more practical and became a good bilingual secretary.”

By then we were living on a large boulevard. Our lawn touched the neighbour's, whose little Chihuahua had fun digging up the flower bulbs Mom had planted with her new flowery cotton gloves. My father had been promoted to District Manager and his company was going to give all the children a nice Christmas gift.

The kitchen in the new house was still the largest room in the house. One day, through the window over the sink, I saw our neighbour dipping an apple on a thin stick into a pot of bright red, smouldering liquid.

- “It’s a taffy apple," said my brother, who once ate one in the yard of the John XXIII High School. “It’s the custom around here to make taffy apples in September.”

In the living room, my mother talked with her sister-in-law Juliette. At 45, she had taken up painting classes, going twice a week to the basement of the Church of Saint-Nazareth, where she painted with gouache under the supervision of a real painter. I heard Mom say that she was going to look into macramé or pottery classes. She wanted to make friends and talk about her plans – decorating the living room and buying the beautiful rocking chair whose picture she had cut out of the Eaton's catalogue.

Aunt Juliet explained to her how to make her skin look younger. And there was Mom covering her face with a mask of egg yolks and finely crushed peaches. On other days, she’d spread ripe tomato purée on her cheeks and placed two slices of cucumber on her eyelids. Then one Sunday, pancake spatula in hand, she asked Dad for a car.

- “Just for me,” she insisted curiously.

I remember it so well. The lines in Dad's face bent upwards into an unmistakeable big YES. At last, his wife seemed to be doing better.

However, a few days later, when the taffy hardened a bit too much or stuck to the bottom of the pot, mom burst out in anger against my brother, against me and even against the two smallest ones who were amusing themselves at the table dressing up cardboard dolls with paper dresses.

- “Why is life so hard?” my mother shouted to invisible psychologists in the kitchen. “I have no friends, no help and I'm so far from my hometown.”

- “I hate this suburb where the houses are so close together you can hear the neighbours fart. I hate their fancy schools, their kids and the way they waste apples.”

Stunned, we followed behind this screaming tower that had once been our mom, and then watched as she buried herself under the new Kennedy pink chenille throw. Taking refuge in the girls' room, with brother kneeling in front of the statue of the Immaculate Conception, we prayed that the illness would not return and take over her body again.

Returning home from Quebec City, Dad tried to console her. When Grandpa finally arrived to help out, he distracted us with stories of the Micmac, who originally lived on the lands just south of the Gaspé Peninsula.

- “The name Gaspésie,’” he explained, “comes from the Iroquois word gachepeg, which means ‘land’s end.’ The Gaspésie is like a point that sticks out into the sea.”

- “Tell us, Grandpa, can eczema be cured?”

And Grandpa Frédéric continued his story, recounting how the Micmac met Jacques-Cartier on his first visit in 1534. Then, placing an old quilt on his shoulders, grandfather began to parade down the hallway. Proud and noble, he imitated Donnacona, a great indigenous chief when he protested against Cartier's taking of the land and the erecting of his famous cross on the Gaspé cliff. We followed grandfather to Mom’s room. Jérôme played the role of Donnacona’s oldest son, and he had to hold his spear as the chief toppled the imaginary cross at the centre of our parents’ bed. Appointed as the other son, I lifted Grandpa’s cloak as he pleaded with the Great Manitou.

When things got tense between Mom and Dad, Grandpa brought the Donnacona camp down to the basement. He spread the quilt over the cement floor and we sat in a circle around him. He smoked a large invisible peace pipe, slowly inhaling the wise advice of the benevolent spirits.

- “This afternoon," said Grandpa, “Donnacona will tell you the story of a young orphaned Iroquois girl who was turned into a seagull for trying to rescue a young Huron condemned to die of hunger and bound in chains on the highest peak of the Gaspé.”

- “What’s a Huron?” asked the youngest.

- “A member of another tribe than ours,” replied my brother, as a true son of Donnacona would.

And Grandpa continued to tell the story of the Iroquois orphan until the Great Manitou brought peace to our parents’ room...

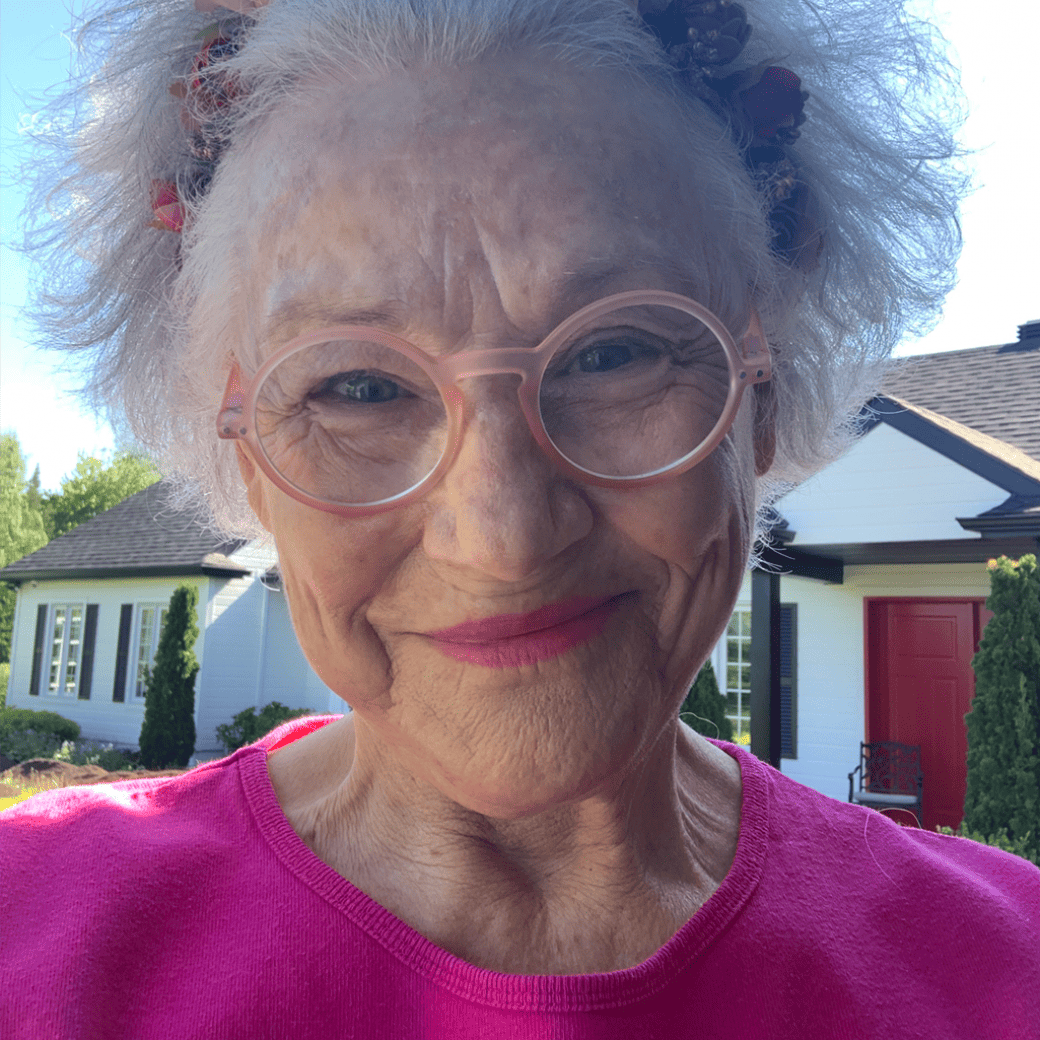

Cora

❤️

Psst: “Some of the world’s best educators are grandparents.”

Dr. Charlie W. Shedd (1915-2004)