An enterprising grandmother

This is a story I learned through the crooked branches of our genealogical tree. Ancestors Charles-Louis and Philomena Van Zandweghe crossed the ocean from Belgium to begin a new life at the turn of the 20th century. With their half-dozen children, two of Charles-Louis’ brothers and a group of friends made up of priests, a baker, a carpenter, a butcher, a notary and linen weavers, they settled in the village of Caplan, in the Gaspé wilds. The call of adventure, the chance to own farmland and the quest for a better life were enough for the Belgians to venture to this foreign land. The place became known unofficially as “Little Belgium” and later took on its present-day name, Saint-Alphonse-de-Caplan.

That is where the heroine of my story was born, on October 1, 1884, some 15 years before the Belgians set foot in the province of Quebec. I can hardly imagine the psyche of this young girl, condemned to live a dirt poor life on an arid earth that the settlers at that time had nicknamed “The Ordeal.” Her thoughts, her beliefs and her outlook were forged in a village where logging was the main activity. She hung around lumbermen, farmers, children who attended a one-room schoolhouse, a teacher and probably a priest.

During her formative teenage years, I suppose the young girl developed her own identity, ideas and feelings. I would trade in all my wisdom to the devil to discover how she became such an admirable young woman. Unfortunately I have little information about her life to recount. What I do know is that her life took a turn when the Belgians arrived. For better or worse, dear readers, it’s up to you to decide.

One beautiful Sunday morning, a smartly dressed man caught the attention of my heroine standing on the church steps. It was obvious that this stranger wasn’t a local. The young woman inquired and learned from the church official that a liner had just docked in Bonaventure. “Another shipload of Belgians!” she exclaimed.

Wanting to make a good impression the next time she saw the stranger, she made herself a pretty pleated skirt with a bolero from the dress of a great aunt who’d passed. She waited anxiously for Sunday to arrive. A short while later, they were married on September 8, 1913. The beautiful bride was 29 and her handsome George, a year younger.

For the sake of this story, let’s call the husband “Big George,” the one who never got his hands dirty. My leading lady quickly understood that her man preferred to show off his expensive clothes rather than weed the garden by hand. Big George hated manual labour. He always had a good excuse to get out of tilling the land, hauling firewood, feeding the animals, etc. He enjoyed going to the village, drinking gin at the general store, mailing a letter or taking over two hours to find himself a prettier, younger fish to fry and play with.

All Big George was good for was helping to increase the population of the immigrant town, which was in desperate need of strong, able arms. Convinced he was doing his fair share of efforts, he got his wife pregnant eight times in 12 years: four boys and four girls to feed. It became necessary to extend the kitchen table, quadruple the size of the garden, bleed three pigs a summer, salt seven to eight barrels of cod and purchase a second horse, two new cows, brood hens, a few dogs, a metal bathtub and sensibly priced fabric to dress the kids.

My heroine often cried in silence, especially when Big George had been drinking and made sexual advances that were no longer welcome. Rain or shine, she would avoid him at all costs. She cooked, sewed, did the laundry, cleaned the house and went out after dinner to weed her garden. I can picture her tired body, deformed, her arched back, her chapped hands, her cracked fingers uprooting the weeds while praying to God that the earth would feed her flock of children. Alone in her garden at dusk, she’d confide her feelings to the scarecrow. With everything she had sown, she’d tell herself, the kids would at least eat well and there’d be enough left over for canning.

At the end of September, the poor exhausted mother had to be taken to the apothecary in the neighbouring village. She’d fallen while carrying a huge bucket of boiling water for Big George’s bath. Her arms, abdomen and legs were scalded, causing her great pain. She needed ointment. While she sat on a stool waiting, she overheard a few men talking about the gold mines in Timmins, Ontario. Many able-bodied men, both young and old, were headed there to make good money. The conversation didn’t fall on deaf ears. This hard-working woman decided her four sons would become miners and her four daughters would help her open a restaurant for the mines’ workers.

A few days later, the woman confided her plan to the parish priest. She’d leave for Ontario with her sons who were old enough to work at the mines. She and her daughters would open and run a restaurant to feed the miners. “Make fishermen, farmers or priests of them instead!” replied the man in the neatly ironed black cloak. “God needs middlemen down here to save our souls.” The wife and mother didn’t reply. She thanked the priest for his sound advice and said goodbye.

As for Big George and his new prince consort attire, the older he got, the more he hated Saint-Alphonse-de-Caplan. When his wife suggested he visit his clergymen cousins who lived in Rhode Island, he quickly seized the opportunity to jump ship and escape “The Ordeal.”

Very few people noticed the quiet departure of the woman and her eight children. They made their way to Montreal first, and then boarded a train bound for Timmins. When she reached her destination, my heroine was buzzing with enthusiasm. Two days after their arrival, she laid eyes on a large, abandoned house, not far from the mining facilities. At the notary’s, she shrewdly weighed her purse’s contents and offered half the requested amount. The boys started at the mine and the girls helped their mother in the kitchen and waited tables.

The business immediately flourished thanks to the mother’s culinary talents and the “special favours” that some of the accommodating waitresses provided to the best male customers in the rooms above the restaurant.

And so, after so much misery, that’s how my heroine improved her circumstances. I’ve often wanted to tell this story before, but hesitated each time. I was ashamed that a woman in my family had relied upon “special favours” to earn her bread. She died in Kapuskasing, Ontario, on July 5, 1967, shortly after I turned 20.

Her name was also Cora.

She was my father’s mother.

And my enterprising grandmother.

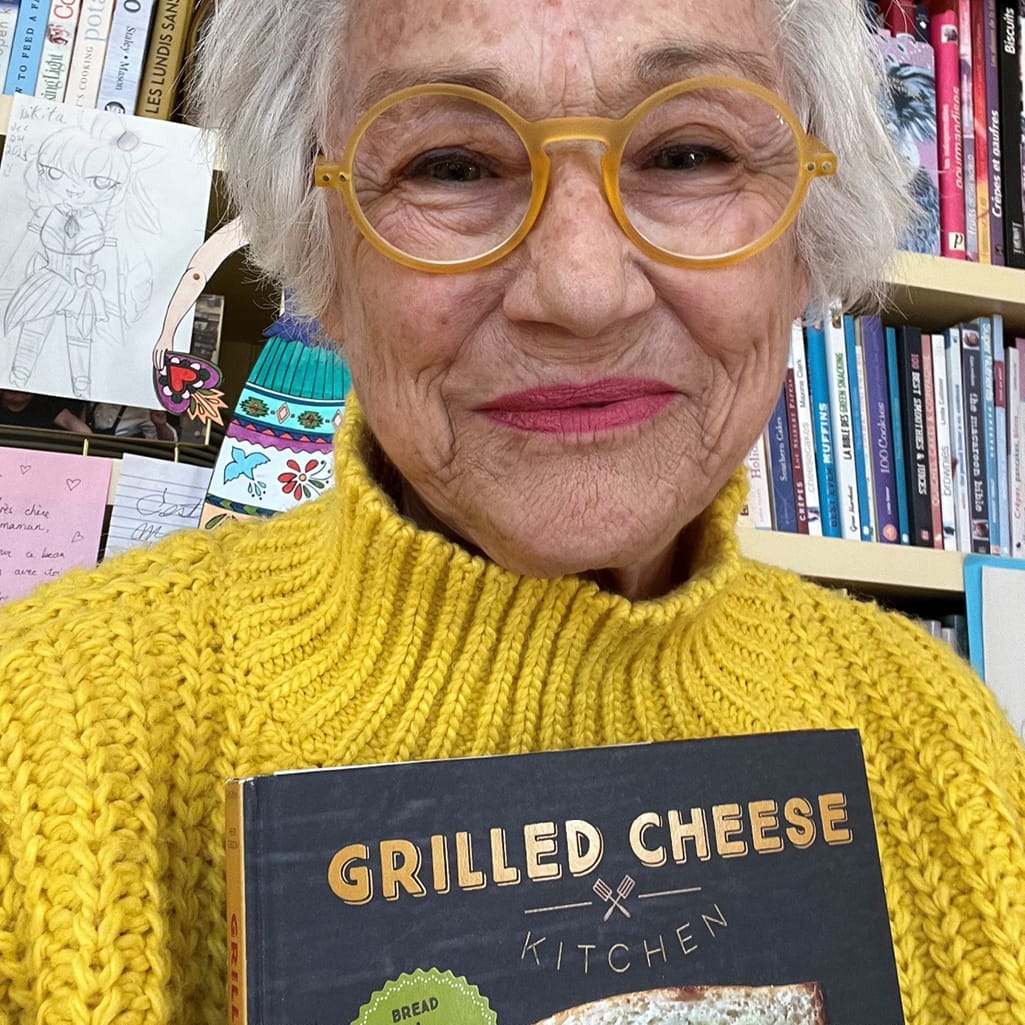

Cora

❤